After the Storm Five Years of Performance Management

By Marc Effron, President, Talent Strategy Group

I grew up in a small town outside Seattle, Washington, and on warm summer afternoons I’d often see grey and white thunderclouds rise above the peaks of the distant Cascade mountains. As sunset approached, these “dry” storms would deliver brilliant flashes of lightning and booming claps of thunder but precious little rain.

I think of those summer storms as I reflect on the squall that recently rolled through performance management. Like those early evenings near the Cascades, the last five years of debate have been marked by deafening noise and flashing light. Now, as the sky clears, we see that the storm’s furor far exceeded the change that it created.

The Storm Approaches

In July 2012, Vanity Fair magazine published a lengthy article that described Microsoft’s corporate decline and blamed its then-CEO Steve Ballmer for destroying its culture. A primary cause cited for the decline was Microsoft forcing managers to distribute employee performance ratings in a ratio of 20%, 70% and 10%. Despite the fact that many successful companies used a forced or managed distribution of performance ratings, the article and subsequent coverage of it highlighted this single factor as pivotal to the computing giant’s fall from grace(1).

While it wasn’t novel to criticize performance management, the Vanity Fair article was the first broadly heard thunderclap in the approaching performance management storm.

Even while the article fundamentally erred in blaming performance ratings for Microsoft’s poor corporate performance, it unintentionally highlighted the real issues that undercut the effectiveness of performance management.

The article quotes Steve Stone, the founder of Microsoft’s technology group as saying, “We couldn’t be focused anymore on developing technology that was effective for consumers. Instead, all of a sudden we had to look at this and say, ‘How are we going to use this to make money?’” It’s not unusual for technologists to value the technical attributes of a product over its commercial merits, but it seems reasonable that the leader of Microsoft’s technology group should be accountable to produce a commercially viable product.

Another former Microsoft engineer quoted in the article said that the Microsoft review process, “was always much less about how I could become a better engineer and much more about my need to improve my visibility among other managers.” This statement sounds like very valuable advice to someone who is technologically competent but needs other key capabilities to become more successful at work. The technologist’s comments and the engineer’s disappointment suggest that the purpose of performance reviews wasn’t clear to employees at Microsoft.

Bloomberg BusinessWeek fueled the storm’s growth with the November 2013 article, “Performance Reviews: Why Bother? The worthless corporate ritual that is the annual performance review(2).” Playing off the Vanity Fair article, Marcus Buckingham published a Harvard Business Review article in December 2013 which praised the Microsoft decision and declared traditional performance management dead, declaring in his opening statement that “Obviously we need a new system(3).” Similar articles followed that argued that performance management and performance reviews were unfair, out-of-step, bureaucratic, backward-looking, disengaging and not aligned to the needs of a modern organization.

Facing off against journalists and consultants calling for bold changes were the successful business executives who supported traditional performance management. Former GE CEO Jack Welch said, “Most experienced businesspeople know that ‘rank and yank’ is a media-invented, politicized, sledgehammer of a pejorative that perpetuates a myth about a powerfully effective real practice called (more appropriately) differentiation.”

Welch fought against those who argued that stack ranking and pay differentiation devalued teamwork. “If you want teamwork, you identify it as a value. Then you evaluate and reward people accordingly. You’ll get teamwork; I guarantee it.”

David Calhoun, then-CEO of Nielsen Holdings and former vice chairman of GE, said that he used and still supported stack ranking, saying, “I’m a fan of relative ranking, a big fan. At GE there was only one objective, and that was to force honesty. … And there’s nothing that quite forces that more than employees knowing that they expect to know how that manager ranks them, and then asking that manager, ‘Tell me where I rank and tell me why(4).’

The approaching performance management storm was partly driven by legitimate dissatisfaction with a time-consuming, bureaucratic and often uncomfortable process. It was also fueled by the social perspective of some individuals that differentiation (or acknowledging differentiation) was harmful to a corporate culture and that the purpose of performance management wasn’t primarily to drive higher corporate performance (5).

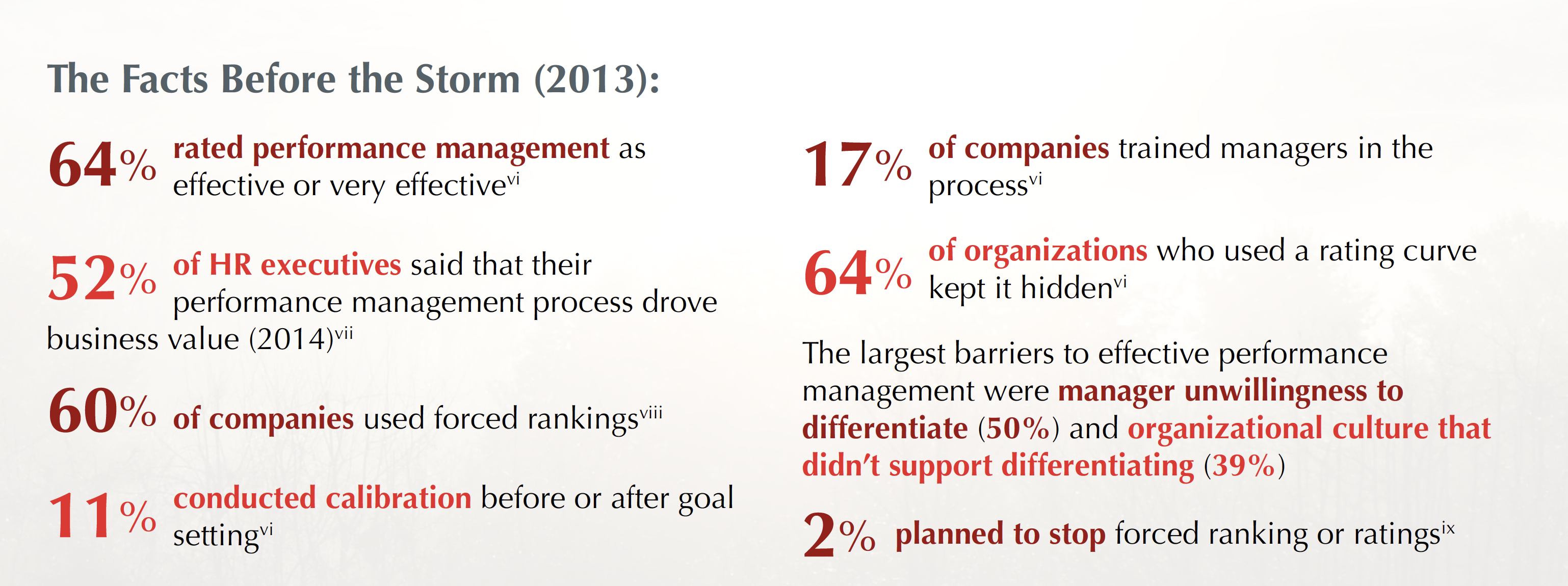

While the media focused on rating and rankings (an issue that few companies were actively considering according to Exhibit 1), missing from the business and HR media discussion was any mention about setting goals or coaching, manager and employee accountability, company financial success or the science of individual performance. And then came the deluge.

The Storm

The storm clouds billowed higher with the August 2014 publication of “Kill Your Performance Ratings” in Strategy+Business magazine. This article claimed that performance ratings had a number of deleterious effects including inciting a fight or flight reaction in employees and causing average-rated employees to feel “disregarded and undermined (10).” But the full brunt of the storm was felt in April 2015 when Harvard Business Review published a cover story on Reinventing Performance Rankings and teased that it would provide a “radical new way to evaluate talent (11).” It was a bright flash of lightening that promised a refreshing rain.

The facts and science on performance management varied sharply from the idealized version presented by these magazines. There was a significant logical gap between observing a fight-or-flight reaction to ratings and claiming that we should redesign human resource processes because of that. The HBR article told the story of a grossly overcomplicated performance management approach at consulting firm Deloitte and how they had shifted from providing an overall annual performance rating to more frequently rating employees on four questions including, “Given what I know of this person’s performance, and if it were my money, I would award this person the highest possible compensation increase and bonus.” While Deloitte’s solution felt like a welcome improvement, it was far from a “radical new way to evaluate talent.”

The consulting firm Accenture was also lauded for radically changing their approach to performance management, but in reality, very little changed. Performance Management became Performance Achievement. Employees were still evaluated against their peers, just a more relevant set of peers. Ratings criteria still existed, just with different names. The primary change was team members’ ability to get faster feedback and create new priorities more easily. These may have been helpful improvements but they triggered questions and concerns about whether one could replicate these approaches in non-consulting environments.

Changes From The Storm

While the storm had been loud, it didn’t appear to produce much rain. So, what effect did the storm have if the radical shifts reported didn’t actually take place? We see three primary outcomes:

More frequent conversations: There was consensus among managers, employees and HR that annual feedback wasn’t frequent enough to either drive awareness of performance opportunities or higher performance. Many companies have addressed this by moving to a quarterly or more frequent performance discussion cycle. Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan Chase have implemented systems that allow faster feedback after projects. Consulting firm PwC implemented a tool called “snapshots” that provides team members with a quick assessment on five characteristics including leadership ability and business acumen. Employees are free to request one at will. Ridesharing company Lyft uses a program that polls an employee to assess the performance of a colleague who they’ve recently met with (12, 13, 14).

For those who thought that the storm would usher in a kinder and gentler era of performance management, more frequent conversations have shined a brighter light on low performers. Kimberly Clark implemented a more frequent feedback system as a part of a fundamental change in performance management and company culture. According to the Wall Street Journal, “In 2015, Kimberly-Clark retained 95% of its top performers. Among the employees whose work was rated “unacceptable” or “inconsistent,” 44% left the company voluntarily or were let go.” The paper adds that, “One of the company’s goals now is “managing out dead wood,” aided by performance-management software that helps track and evaluate salaried workers’ progress and quickly expose laggards (15).”

Part of the shift to frequent conversations is driven by different expectations within the workforce. A recent survey showed that about 65% of millennials said they’d prefer formal feedback at least every six months compared to about 40% of boomers (16).

Some process simplification: While it’s difficult to objectively assess the extent to which processes have been simplified, our consulting engagements with large clients, what we hear at our Talent Management Institute, and our conversations with HR executives suggest that some firms have taken a hatchet to parts of performance management. Pages have been removed from forms. Competency models have been stripped down. Formulaic rating systems have been shifted to discretionary ones.

We suggest that these changes didn’t result from the storm itself, but from HR leaders growing acknowledgement that complex processes and HR fads were severely undercutting HR’s legitimacy. These changes are welcome but our experience is that many organizations still have significant progress to make in both their design and operationalization of performance management.

Ratings dropped by some, then reversed; research says “don’t”: The brightest flash and loudest noise in the performance management storm was the claim that performance ratings were a relic and being dropped by many companies. The adherents of this approach cited a short list of companies that had dropped ratings, including Microsoft, Adobe and Juniper Networks, as proof of the trend. And, just when it appeared that the ratings storm would intensify, the winds suddenly died down. In the ensuing calm, the damage started to appear:

- There are some outliers who went ratingless, like Adobe, and saw very strong financial performance. However, many others that cut the process, including Juniper Networks, GE and The Gap, are among the stock markets’ worst performers since then.

- Rumors emerged, and were later confirmed, that no-ratings bell-weather Microsoft actually used ratings to determine compensation. They simply didn’t tell their employees that this process existed.

- Companies that were lauded for dropping ratings, including Medtronic, Conagra and Intel, reversed their decisions and reimplemented a traditional ratings-based approach (17).

- In November 2016, Harvard Business Review published an article by Facebook HR leaders titled “Let’s Not Kill Performance Evaluations Yet,” where they stated that 87% of their employees wanted performance ratings. The authors said that the company kept ratings to ensure fairness, transparency, and development.xviii Google joined the debate by stating that they had carefully studied the rating issue and decided to use a traditional 5-point rating scale.

- In November 2016, Gartner (formerly CEB) released the results of their large research project that compared outcomes of companies that had dropped ratings with those that had not. Their study found that companies without performance ratings had lower engagement, lower quality performance conversations, fewer feedback conversations and less happy high performers (19). A USC Center for Effective Organizations study also found that ratingless performance systems were the worst option among a variety of design choices (20).

After The Storm

While interesting to watch, the storm did little to change the landscape of performance management. Many organizations are left with slightly changed approaches. Others are more confused than they were before about what elements to change and how. More importantly, many companies still don’t have in place the fundamental, science-proven elements necessary for successful performance management.

The challenges ahead include:The objective of performance management is not clear: Performance management is a tool to solve a problem but few organizations have defined the problem they’re trying to solve. The storm put a spotlight on this issue, with one group of professionals saying that performance management wasn’t sufficiently developmental and the other side saying that development wasn’t the purpose of performance management. Without a clear purpose, it’s difficult to create a process that generates results.

Goal setting is unfocused; not powerful: It is uncommon to find organizations where managers have mastered the ability to set only few, large goals. The science is clear that this approach will deliver higher individual performance by increasing motivation and higher corporate performance by aligning individual efforts with companies’ needs. We regularly see managers who have 10 – 15 goals, goal setting being used as a project planning tool and goals being written specifically so they can be achieved.

Goal quality is highly variable: largely unchecked: Few organizations maintain a process to ensure that goals are written at an acceptable level of quality and specificity. There is a misguided obsession to get managers to enter goals into a system but typically no effort to review the quality of those goals once they are entered. Simple, fast techniques like manager-of-manager goal audits or goal calibration sessions are rarely used.

Goal setting skills are not taught: Many organizations offer a PowerPoint deck, video or instruction guide to help managers and employees set goals. We find the quality of these tools is highly variable at best. Almost no organizations require managers to attend an in-person goal-setting training course to learn, practice and get feedback on how to set a high-quality goal.

Feedback is irregular and of variable quality: After goal setting, feedback is the most performance-driving element of performance management with rich science that supports its power. We see companies too often focus on the feedback process rather than the effectiveness of the outcome. There is no measurement of feedback quality or the change in individual performance.

Accountability is low throughout the process: The thread that weaves through the elements above is the lack of HR and manager accountability throughout the performance management process. While there is often accountability for actions (enter goals, hold a review) there is rarely any accountability for the quality of the action or its outcome. Goal quality isn’t evaluated. The quality of the coaching conversation or performance review conversation is not measured. The manager’s effect on the employee’s performance is not assessed.

The Next Storm

With little changed despite the commotion, what will finally help performance management to deliver the high performance we know is possible? We believe the three largest levers are:

Science-based simplicity: I often give a short quiz to line and HR leaders when I present or teach about human performance. The questions include whether employees will work harder on goals they set themselves, whether larger goals will create more motivation and other items that are scientifically proven to be true. About 40% of the groups will answer the questions correctly.

There is still more folklore than fact in how most leaders manage performance. The HR leaders who design these processes are sometimes deafened to the conclusive science by the loudness of the storm around them. HR leaders need to better understand the proven science of human performance so they can do more of the right things and more critically evaluate each new leadership fad.

They then need to apply that science in the simplest possible way to ensure that it’s executed in their organization. If we know that having a few, big, aligned goals will increase individual performance, what will we need to do to ensure that everyone in the organization has those. Radical process simplification is a start, but it requires the recommendations below also be implemented.

Capability-building: Managers and employees need to become more skilled in setting a few, big goals and coaching for performance. These are not difficult capabilities to learn but require more than a hand-out or an on-line video. Managers need to be trained, in-person, on a simple approach to identify the few largest contributions they can make to their organization. They need to be given a chance to practice that new skill and get specific feedback to improve their capability. Simple tools like 2+2 coaching must become the standard approach to enable more frequent and more powerful feedback conversations.

Accountability through Measurement: Managers and employees need to have one clear accountability for each phase of performance management – goal setting, coaching and reviews. That accountability can be enforced using a one-question assessment of managers for each key step in performance management. That question can be as simple as, “In the past 90 days, have I had a feedback conversation with my manager that helped me to meaningfully improve my performance or behaviors?” Managers need to understand that your company is serious about performance management and that you’ll measure their outcomes, not their efforts, in this area. They must know that good things will happen to them if they execute the process and less than good things will happen to them if they don’t. The Accountability Ladder provides a great way to assess if there’s enough accountability in your process to drive them to act.

The last storm offered us flash and noise with little change. The next storm can help organizations to deliver high quality products, better customer service, faster innovation and the many other benefits that come from higher individual performance. It can help individuals to learn faster, earn more and increase confidence in their abilities. To get to these outcomes we must agree that the goal of performance management is to increase performance and that science-based simplicity is the only sure way to achieve that goal. We must also stand guard against those who suggest solutions based on shaky science or who appeal to our personal convictions, rather than prove their case with facts.

It’s fine to be entertained by the lights and noise but it’s time to shift our efforts to ensure that performance management begins to increase performance.

1) vanityfair.com/news/business/2012/08/microsoft-lost-mojo-steve-ballmer

2) bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-11-07/the-annual-performance-review-worthless-corporate-ritual

3) hbr.org/2013/12/what-if-performance-management-focused-on-strengths

4) shrm.org/ResourcesAndTools/hr-topics/compensation/Pages/Stack-Ranking-Microsoft.aspx

5) talent-quarterly.com/is-meritocracy-overrated-use-with-caution-john-boudreau

6) towerswatson.com/en-GB/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2014/03/Pulse-Survey-on-Performance-Management

7) deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/human-capital-trends/2014/hc-trends-2014-performance-management

8) forbes.com/sites/petercohan/2012/07/13/why-stack-ranking-worked-better-at-ge-than-microsoft

9) i4cp.com/ trendwatchers/2013/10/31/performance-management-sticking-with-what-doesn-t-work

10) strategy-business.com/article/00275?gko=c442b

11) hbr.org/2015/04/reinventing-performance-management

12) wsj.com/articles/the-never-ending-performance-review-1494322200

14) wsj.com/articles/how-four-companies-evaluate-employees-year-round-149432220515

15) wsj.com/articles/focus-on-performance-shakes-up-stolid-kimberly-clark-1471798944

16) stories.quercusapp.com/why-millennials-want-frequent-feedback-747a47b8041

17) wsj.com/articles/the-trouble-with-grading-employees-1429624897

18) hbr.org/2016/11/lets-not-kill-performance-evaluations-yet

19) news.cebglobal.com/2016-11-07-Performance-Reviews-Dont-Remove-the-Ratings

More About The Author:

- Marc Effron, President, Talent Strategy Group

- Marc founded and leads The Talent Strategy Group and consults globally to the world’s largest and most successful corporations. He co-founded the Talent Management Institute and created and publishes TalentQ magazine. He co-authored the Harvard Business Review Publishing best-seller One Page Talent Management and 8 Steps to High Performance.