Building Great Talent Managers: The 4+2 Model

Post content

by: Marc Effron and Jim Shanley

The answer never changes. Every year a global strategy consulting firm will survey executives to ask which topics are most important to them. Every year “having more better quality talent” is a top three priority.

Organizations have progressed unevenly towards achieving that goal. Our global experience as consultants and practitioners finds some organizations covering significant ground and others very little.

It may surprise you that the organizations that have made great progress don’t have larger budgets, better technology or fancier processes than the ones that have achieved far less.

We find the differentiating factor in nearly every successful talent-building organization comes down to this: they have talent-building HR leaders.

Talent-building HR leaders

Talent-building HR leaders differentiate success for an obvious reason. Most HR organizations are incredibly similar.

Most HR organizations have the same organization structure and operating model and the same strengths and weaknesses within it.

We know from our research and consulting that most HR organizations have the exact same practices for growing talent. And, we know that most of them don’t follow through to get the true power from those practices.

Most HR organizations use one of the primary HR software suites and each likes to complain about theirs.

There’s really nothing left to differentiate talent-building success in most HR organizations except for the quality of the HR talent-builders in our department.

So what differentiates those talent-builders?

The Talent-building HR leader (4+2)

We first asked that question more than 15 years ago to top CHRO’s at a meeting we hosted at the University of North Carolina. These executives were complaining that there weren’t enough talent-building HR leaders available to hire.

They asked us (the authors) if we would start a course to teach HR leaders to be talent builders. We said we’d consider it, but first they would have to define a “talent-building HR leader.”

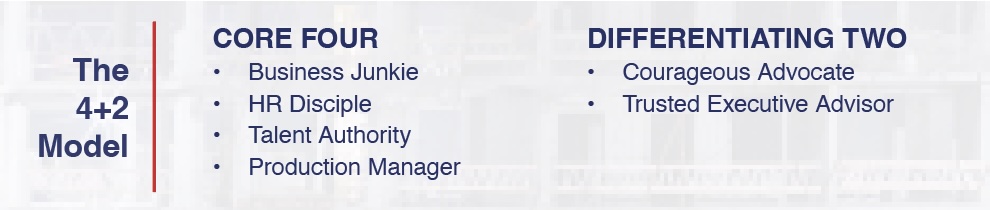

After multiple rounds of interviews with them, other CHROs and top talent executives, we distilled their collective thoughts into the 4+2 model. The course they asked for became the Talent Management Institute, which has now graduated more than 7,000 leaders.

That model’s six characteristics differentiate a talent-building HR leader. We consider four of these to be core – the proverbial “price of admission” required to operate at an acceptable level of effectiveness. Being great at these will make an HR leader technically competent at talent-building.

The other two are factors that separate the great from the merely very good. It is these two that elevate talent-building HR leaders to their highest level of effectiveness and allow them to shape the talent agenda in their organization.

Over the years we’ve reviewed and tested the model to see if factors needed to be changed or updated. We’ve found, and validated with HR and business leaders globally, that these six factors still differentiate the best.

The Core Four

Business Junkie: We list this factor first because it’s the essential starting point and “knock out” factor for being a great HR talent-builder. The Business Junkie both knows business and loves business.

Great talent builders understand at a detailed level how their business or organization operates. They understand the company’s strategy, how the products or services are produced, how the R & D process operates and how the company goes to market.

They can pull apart the company’s (or any other company’s) income statement and balance sheet, and are able to trace human capital decisions back to the relevant line items. Their understanding comes from first–hand involvement in the business – sitting through marketing meetings, wandering the floor at the factory, or going on sales calls.

That level of knowledge allows an HR leader to have business conversations with business leaders. It builds credibility and ensures that the HR leader’s agenda flows directly from what the business needs to thrive.

In addition to knowing their business, talent-building HR leaders genuinely love business. They enjoy waking up each morning to participate in the capitalistic pursuit of making and selling things that produce a profit for their company, jobs for their employees and returns for their shareholders.

Far from being “people focused” and reluctant participants in their companies, they advance a business-first agenda, in which they are responsible to get the best return from that corporation’s talent investment.

If you’re not in a for-profit organization, you should be able to display the same knowledge and love for the mission of the organization that you serve.

HR Disciple: An HR Disciple can think holistically about how to solve HR problems because they have had diverse experiences across the function. They’ve also demonstrated their capabilities in a variety of scenarios from turnarounds to new teams to different geographies.

According to the HR executives we interviewed, there’s no substitute for broad based experience to grow one’s capabilities as an HR Disciple. Many cited executive recruiting experience as a great way to calibrate the gold standard for high performing talent.

Exposure to the other HR specialty areas (compensation, analytics, organization development, etc.) is equally important to ensure the talent-building HR leader has a holistic understanding of how those levers interact to drive performance.

Another critical differentiator? Multi-company experience. There’s just no better way to gain perspective and depth than by seeing how HR challenges are handled in operating environments and under different business cultures.

Those desiring success in this field should actively seek out assignments, projects and other opportunities that broaden their experience in both different HR disciplines and different operating environments.

No matter how superior one’s technical HR skills are, without this additional knowledge and experience it will be difficult to develop the credibility and perspective needed to excel. Given the current mania around AI, it’s helpful to mention that we’d include facility with it under this factor.

Production Manager: Some in the HR and talent management field think of themselves as experienced “craftspeople,” building individual leaders by hand in a labor of love. The best in the field know that they are actually the production line managers on the talent factory floor.

Their job is to build and operate a process that turns out leaders at scale who meet the agreed upon specifications, in the approved time frame. To them, the “talent production line” is not an analogy – it’s reality.

They approach their task with the same disciplined approach to process management as any other production leader. They understand the raw materials available to them, the tools that can most effectively cut, shape and polish that material, and how to ensure that the finished product meets quality standards and is distributed appropriately. They know how to keep the production line moving to produce leaders when needed.

Talent Authority: Great talent leaders know their talent, cold. When the CEO unexpectedly calls asking for a slate of candidates for a role, the talent-building HR leader can immediately list five names along with their strengths and weaknesses. The most expensive HR technology is no substitute for a talent leader’s nuanced knowledge of their charges.

A successful Talent Authority also has a great “eye for talent.” As subjective as that might sound, certain individuals have a talent for selecting talent. They understand what it takes to succeed in a given role and have the ability to quickly assess how well a given candidates fits with those needs.

This likely stems from combining a deep understanding of the business, its culture, and the patterns of past success, with an ability to ascertain how well someone would fit with the intellectual, cultural, political and relationship-based factors of the job. It’s tough to be a talent authority without this capability.

Becoming a talent authority only happens when the talent leader has a deep, personal knowledge of the organization’s talent. This means having one-on-one meetings with key talent where the HR leader builds trust as they gather information about leaders’ careers, their ambitions and their management style.

They must then integrate that information with all the other data they have about that leader – derailer factors, business performance, engagement performance – into a comprehensive 3-dimensional leadership profile. That effort requires a large investment of time, but yields great returns through more accurate and timely talent decisions.

The Differentiating Two

If you become skilled as a Business Junkie, HR Disciple, Talent Production Manager and Talent Authority, congratulations! You are highly technically capable and likely have elevated yourself to the 75th percentile of HR leaders.

But. . . you aren’t yet a talent-building HR leader because you haven’t yet proven you can influence anyone to take action on a talent agenda. Influence matters as much as technical capability.

Technically astute people often hate to hear that statement because they believe that their technical prowess and output from it should be sufficient to convince tough business leaders. It is not.

Every product you buy has been marketed to you. There are stories upon stories of technically superior products that lost in the market to better marketed ones. No matter how technically sharp you are or how technically perfect your “product” is, it does not matter unless you can sell it to a decision maker.

The Differentiating Two are the factors that elevate you from a technical expert to an influencer of the executive agenda. Those who have them are trusted advisors to senior leaders, often including the CEO.

Their guidance has meaningful impact on the most critical talent choices made in the organization and, therefore, on the company itself. They provide insight and coaching to top leaders that is compelling enough to actually effect change.

The two key capabilities they demonstrate are:

Trusted Executive Advisor: The talent-building HR leader demonstrating this behavior provides wise counsel on talent issues in a way that considers their client’s ego, their personal hopes and fears, and reflects a deeper understanding of the organization’s financial, operational and political realities. This requires that the HR leader:

- Is professionally credible: Professional credibility starts with demonstrating the Core Four we discussed earlier. The credible talent-building HR leader can integrate those ingredients in a way that allows the leader to continually make the “right” talent decisions for the organization. This includes being able to persuasively present and argue for a position using the right balance of facts and emotion. Without that capability they are destined to remain a technical specialist.

- Forms strong executive relationships: The quality of an HR leader’s personal relationships with senior executives will determine whether they become a trusted advisor on talent issues. That strong relationship can only happen after the senior leader trusts that the talent leader has their best interest at heart.

To get there, a talent-building HR leader will need to demonstrate that they understand the executive’s personal and professional agendas and that they respond to the executive’s ego needs. The talent-building HR leader will increase the relationship’s strength after each interaction where the executive sees that they genuinely represent his or her best interests.

Courageous Advocate: The Courageous Advocate has a theory of the case about why specific talent choices should be made and they are “appropriately aggressive” in voicing that opinion.

A difficult capability to master, many talent-building HR leaders fail on their path to greatness because they over or under use it. A Courageous Advocate:

Has a Theory of the Case: A theory of the case is a fact-based, brief, logical and credible argument about why a talent decision should or shouldn’t be taken. It is the concise expression of a deeply held viewpoint on why talent succeeds, the best way to develop talent, why talent fails and the learnings from hundreds of other talent interactions.

A theory of the case might be that Mary can succeed as a new general manager even though she’s never led teams before because:

- Point #1: She is highly motivated to succeed in that role and she’s breached similarly large gaps in her career development driven by that motivation.

- Point #2: Her personality characteristics are consistent with leaders who have successfully led teams through challenging times.

- Point #3: We have strong development and support mechanisms for general managers in our company.

- Point #4: She has a strong functional team around her who will provide support as she learns.

A well-developed point of view is at the core of being persuasive. It should bolster the courage of the talent-building HR leader.

Is Appropriately Aggressive: This phrase captures a variety of nuanced behaviors that differentiate great talent-building HR leaders.

To us, “appropriate” means knowing how to select which battles are worth fighting, knowing in which situations pushing back will be most productive and knowing the politically productive way to bring a potentially incendiary issue to the table.

“Aggressiveness” means not being afraid to voice your opinions, to fight for what you believe is right and not to be afraid to push back just one more time.

The combination of a theory of the case and the appropriate amount of aggressiveness creates a talent-building HR leader who drives the right talent decisions in the right way.

In What Order

We’re sometimes asked, “if influencing is as important as you say it is, why not develop that skill first, before the Core 4?” It’s a reasonable question but one that’s easy to answer.

If you’re incredible at influencing but have no content expertise you’re at best an empty suit with an opinion. Think about that leader who sends you an article they read from a three-year-old Harvard Business Review with a note saying “We really should be doing this.” What do you think of them?

You become that leader if you have no content expertise. As we wrote earlier, you need to demonstrate your technical competence and breadth before anyone should trust your advice about important talent decisions.

The Bar is Higher than you Think

For each of the 4+2 we have a metric (or two) that we use to evaluate an HR leader’s competence. When we ask HR leaders to self assess without telling them the metric, most rate themselves as highly proficient or expert.

Once we describe our metrics, their evaluation drops precipitously. We describe each metric briefly below but in much more detail if you attend our Talent Management Institute course!

- Business Junkie: You can walk your CEO through the financials of your company and explain their relevance in an industry context.

- HR Disciple: You have quality experiences across HR sub-functions, management challenges, lifecycle challenges and, if applicable, geographies.

- Production Line Manager: You can both build the pieces of the talent production line and ensure their execution.

- Talent Authority: If you are an HRBP or talent management leader, you can describe the high performing and high potential leaders in the top 3 layers in your company in a granular way, without notes.

- Trusted Executive Advisor: What’s the “buzz” about you in the executive suite? If I ask a CXO, “Would you trust them with your corporate life?” They answer, “Absolutely.”

- Courageous Advocate: Have you visibly demonstrated this at a time when it mattered to the company and could have hurt your career if you were wrong?

Your Focus

As more HR work becomes automated, the few differentiating HR capabilities will become more and more valuable. With all the talk about AI, it will replace the foundational work of HR, not the elevated, quality and differentiating work described in the 4+2. These few capabilities are where you need to focus your effort and attention.