Reaching for Stars: What you Need to Know about Exceptional Talent

Somewhere above the intersection of high performers and high potentials exists a rare and exceptionally capable type of talent. Their contributions are five times, ten times, up to fifty times larger than the average employee. They’re so rare that you might not have one in your company.

We know that they’re often found in creative and entrepreneurial environments but can thrive in blue-collar environments as well. Their presence sometimes helps and sometime hurts the performance of those around them.

These are “stars” and their unique contribution suggests that you need to know who they are, why they matter and how to manage them. You want to extract their best performance and avoid any potential downsides from their presence.

We summarize below the past decades of great research on stars and integrate our advice about the optimal care and feeding of your stars (if you have any).

What’s a Star and Why Should You Care?

A star is an individual with outstanding performance and high visibility both within and outside their organization.i Both elements differentiates a star, so let’s discuss the importance of each.

Outstanding Performance: Stars produce exceptional output and they produce it more quickly than others.ii That exceptional output shatters the high end of companies traditional performance curves. Stars aren’t a “5” on your 1 – 5 scale – they’re a 10 or 20 or even a 50. (See side bar: What is a Power Law and Why Does it Matter When We Talk About Stars?)

The output of a star can be 5 to 50 times that of an average performer.iii The highest-end multiples are typically in creative or innovation-driven roles that have near complete freedom in how work is done vs. more standardized roles.

For example, a top engineer may write an algorithm that automates millions of tasks, while an average engineer might only optimize a small part of an existing system. An entrepreneur may create a viral product that they sustain far beyond its projected lifetime while a good product designer might create one decent selling product.

Stars can also be found in blue-collar and manufacturing roles even though the more constrained nature of these jobs somewhat limits high-end performance. High performers in these jobs are already 50% more productive than average performers and research shows a “power law” effect can produce stars who are 200% – 400% better performers.iv, v

The multiplicative output power of stars may grow even further as technology advances. There are no studies as of this writing about the power of stars enabled by AI, but we assume they will eventually show that stars who know how to produce outsized results will use technology to further multiply their output.

Highly Visible: Stars are well known in their industry and their increased visibility gives them and their company power.vi This is a critical differentiator of a star vs. a high performer. A shy, unassertive high performer will never emerge as a star or gain any of the power that comes from others knowing their competence.

Stars are known because they are featured in business media, social media, articles, speeches, books, league tables and other public-facing communications.

They have power because they know that other companies would like to hire them. And, they have power because they know their company knows that other companies would like to hire them.

Why should you care about stars? In short, because the research says they add financial value to your company.vii

What is a Power Law and Why Does it Matter When We Talk About Stars?

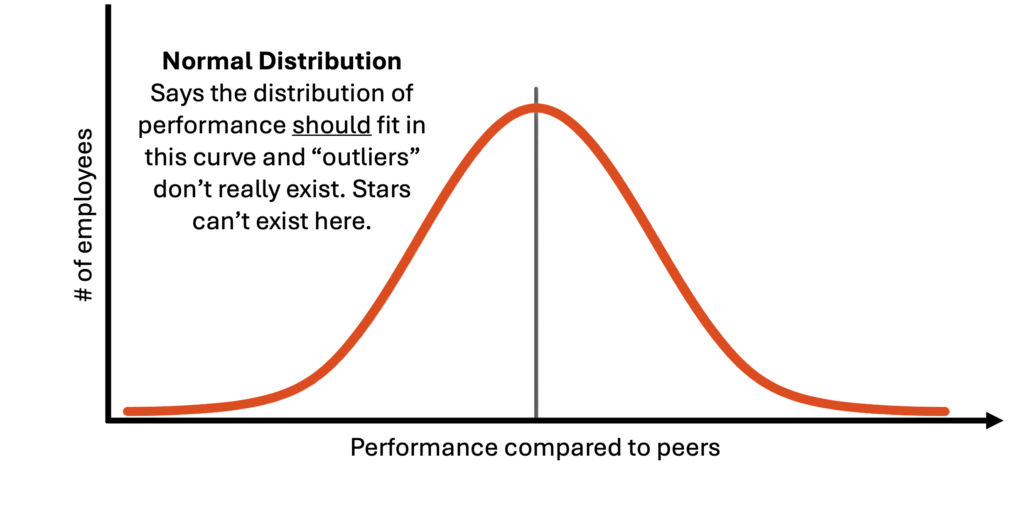

You know that people manager who loudly complains every year that the performance distribution you asked them to meet is wrong? Well, they’re correct, but about the wrong thing.

They’re not correct that their team members are all above average. They probably set goals poorly or over assessed their team. Where they’re right is that the “normal curve” we’ve been trained to use to assess human performance doesn’t accurately capture it.

A normal curve assumes that most of us perform fairly well and that a few higher performers and lower performers exist. A power law curve suggests that performance is not that evenly spread.

Instead, a small percentage of employees contribute a disproportionately large amount of value compared to their peers, who contribute at a decent but meaningfully lower level. If stars exist, they do so at the far end of the power law curve.

The best proof of this comes from research reviewing 198 samples and include 633,263 researchers, entertainers, politicians, and amateur and professional athletes. That research found that 186 of those samples follow a power law distribution.

Do Stars Stay Stars?

A star only has value if they stay a star, so a key question is whether stars stay stars if they switch organizations and over time in their own organization.

If they switch: If a star is only a star in one company, it suggests it’s their team, their company culture or another attribute of their environment that meaningfully contributes to their shine. That reduces their value because they’re now either not as desirable in their own company or to other companies.

Imagine a chef who can only cook in one restaurant, an actor who can only perform in one theater or a sports star who can only set records in one stadium. It’s wonderful that they shine in those limited situations, but it begs the question of whether they are truly stars.

The “portability” of talent was brought into question by Harvard’s Boris Groysberg who showed that star stock analysts’ performance declined for two years after they joined firms similar to their own but declined for five years when they joined weaker firms.viii That suggests that stars are a combination of their own capabilities and those of their company. It also says that there is some raw “star” material that stars bring with them from job to job.

When they stay: We know the three strongest predictors of individual success are cognitive capabilities, select personality factors and ambition. The first two won’t change from role to role, nor should too many elements of ambition. So, unless the star moves to a fundamentally different role in their company or decides they no longer want to be a star, the odds are strong that they’ll stay a star.

How Do Stars Help or Hurt Teams (and Vice Versa)?

There’s mixed research on what happens to other team members when a star joins a team. A study from the investment industry showed that the industry journal rankings of other team members dropped when a star joined the team. The researchers blamed this on the star perhaps undeservingly attracting internal resources away from other team members.ix

Another study showed decreased performance among team members who had a highly competitive mindset once a star entered the team.x A related analysis of professional golfers found that when a superstar played in a tournament, the other golfers played nearly one stroke worse. Tiger Woods’ presence alone would cause players to score 0.2 strokes worse and even worse than that when he was playing extremely well.xi

Conversely, another study showed that a star can increase the performance of those around them, especially if their peers aren’t too senior. That study also showed that adding more stars eventually had decreasing benefit.xii (The “too many chefs” effect, apparently.)

A study of biotechnology firms found that colleagues of stars had higher performance, and that the optimal performance happened when a star had a narrow specialty and was broadly collaborative with their colleagues.xiii Researchers also found that creative stars can elevate the creative performance of their team by integrating and spreading new ideas throughout the team.xiv

So, there’s mixed evidence on whether a star dims or brightens the glow of those around them.

Importantly, teams can help to make or break stars as well. A study showed that teams will support a newly hired star who they feel is self-made but work to thwart one who they believe became a star through political or other unearned means.xv

Star Networks

There’s huge value in the network a star builds vs. just their own personal productivity according to a paper that looks at patents awarded from 1974 – 1998. The research found that companies with more “relational stars” – individuals who were great at both knowledge production and collaborating with others – generated more patents and higher-quality innovations.xvi

The same paper found that companies that relied on stars who had high individual performance but did not have strong networks saw decreased patent development over time.

Why Not Just Hire a Few More “Almost as Bright” People Instead of Stars?

It seems fair to ask the question, “Why not just hire two people who are almost as good as a star?” You’ll likely avoid their ego, they’ll have less leverage over you and there are certainly more of them.

Well, there’s some interesting math when we talk about stars. Two “almost stars” aren’t equal to one star. In fact, 10 “almost stars” aren’t equal one star. Think of it this way: How many “almost Steve Jobs” would it have taken to create the iPhone? How many “almost Taylor Swifts” would it have taken to write and sing Cruel Summer? How many “almost Lionel Messi’s” would it take to be a global soccer (sorry, football) star?

To our power-law, 50x, statement above, stars are not marginally better than the next person. They are in a fundamentally different class of performance.

This truth has clear implications for how you hire and who you retain. That incredibly brilliant, incredibly expensive candidate? They’re likely a far better buy than the “almost” candidate. If you’re looking to cut costs, the “almost thems” are probably the best place to look.

What Happens When a Star Leaves

One of the purest measures of whether a star adds value is what happens when they leave. Researchers looked at star scientist turnover in biotech firms and their findings amplify other studies that show the danger of high performing, less-collaborative stars.

When less collaborative stars left, the firms in the study couldn’t maintain their levels of innovation. However, when the more collaborative stars left, the firms engaged in more exploration and innovation because of the stronger networks that the stars had helped to build.

In a more final measure of a star’s departure, a study examined what happened after 452 star life scientists died. It found that when a star scientist died, there was a 21% decrease in the publications of the star’s former collaborators. It also found that more new ideas emerged in the field after the stars’ deaths.xvii

Implications for Finding, Managing and Paying Your Stars

Stars, by definition, are rare and high performing, likely expensive and possibly a bit difficult to manage. In fact, a recent statistical study claimed that the ideal mix of intelligence, conscientious and emotional stability would only be found in less than 1 in 10,000 people.xviii And, that’s before we consider skills, behaviors and all the other variables that go into making a star.

Given those facts, your first question should be whether your organization needs any stars at all.

If you do, we’d suggest they should only be in a critical role. That role will be one in which higher performance is linearly related to higher results. There’s likely room for stars in those roles since our most recent Critical Roles Report found that only 57% of companies put high performers or high potentials into their critical roles.

What you should you pay a star?

This is where things get tough. There are relative, structural and budget questions to consider.

- Relative questions: Can you pay someone who delivers 20x the value of others 20x the compensation of others at the same level? Traditional bonus and long-term incentive structures are meant to fairly compensate people who perform somewhat above average. They treat brilliant performance and very good performance exactly the same.

- Structural questions: A fair system wouldn’t cap a stars pay at 150% or 200% of a bonus opportunity. If someone or a team of them did something that created a $1B windfall, why shouldn’t that team get $20M or more distributed among them?

- Budget questions: It’s highly unlikely that a manager was given a compensation budget that allows for a star-sized bonus payment. Have you budgeted for, or plan to accrue for, that star’s payment if they deliver a star-sized result?

How should you manage a star?

This seemed like a good question to test ChatGPT’s often-generic management advice. It delivered as expected – not ground-breaking but certainly solid guidance for managing stars or even emerging stars in your group.

The prompt to ChatGPT 4o was: if a professional worker is consistently an exceptionally high performer who likes to be well known for his or her performance, what are some tips for how to best manage an individual like this?

ChatGPT’s response (all bolds in the original): Managing a consistently high-performing professional who also enjoys being well-known for their performance requires a strategic approach. You want to motivate and retain them while ensuring their drive for recognition does not create team friction or ego-driven challenges.

Tips for Managing a High-Performer Who Values Recognition

- Provide Meaningful Recognition & Visibility

- Acknowledge their contributions publicly but in a way that aligns with business goals (e.g., showcasing impact rather than just effort).

- Give them high-profile opportunities (presenting to leadership, leading key projects) to feed their need for visibility in a structured and productive way.

- Ensure recognition is tied to team success as well, so they remain collaborative rather than competitive.

- Keep Stretching Their Abilities

- High performers often get bored easily if not challenged.

- Give them complex projects that push their skills beyond their comfort zone.

- Encourage them to mentor others—this keeps them engaged while reinforcing humility and team contribution.

- Balance Confidence with Self-Awareness

- Provide regular feedback to ensure they maintain self-awareness and don’t develop an inflated ego.

- Use data-driven performance discussions so they stay grounded in real impact, not just perception.

- Encourage them to seek input from peers so they stay open to different perspectives.

- Align Their Personal Brand with Organizational Goals

- If they value being well-known, help them channel that visibility into leadership-building activities (e.g., speaking at industry events, publishing insights, leading cross-functional teams).

- Encourage them to contribute to the organization’s success story, not just their own.

- Set Clear Expectations on Collaboration & Behavior

- Make it clear that team dynamics matter and that a high performer is more valuable when they elevate others.

- Reinforce that leadership is not just about individual achievement, but also about developing others and sustaining long-term success.

- Offer Growth & Future Leadership Paths

- High performers who seek recognition often aspire to leadership roles—give them a roadmap for advancement so they see a future within the organization.

- Help them develop emotional intelligence and people management skills, as leadership requires more than just performance excellence.

In Closing

A star is a rare, highly contributing individual whose performance can help lift an entire organization to new levels. The more we know about who they are, how they interact with their teams, what happens when they leave and more, we can make smarter decisions about if, and when, we should add a new star to our firmament.

References:

i. Call, Matthew L., Anthony J. Nyberg, and Sherry Thatcher. “Stargazing: an integrative conceptual review, theoretical reconciliation, and extension for star employee research.” Journal of Applied Psychology 100, no. 3 (2015): 623.

ii. Aguinis, Herman, and Ernest O’Boyle Jr. “Star performers in twenty-first century organizations.” Personnel Psychology 67, no. 2 (2014): 313-350.

iii. O’Boyle Jr, Ernest, and Herman Aguinis. “The best and the rest: Revisiting the norm of normality of individual performance.” Personnel Psychology 65, no. 1 (2012): 79-119

iv. Aoyama, Hideaki, Yoshi Fujiwara, Yuichi Ikeda, Hiroshi Iyetomi, and Wataru Souma. “Superstatistics of labour productivity in manufacturing and nonmanufacturing sectors.” Economics 3, no. 1 (2009): 20090022.

v. Hunter, John E., Frank L. Schmidt, and Michael K. Judiesch. “Individual differences in output variability as a function of job complexity.” Journal of applied psychology 75, no. 1 (1990): 28.

vi. Oldroyd, James B., and Shad S. Morris. “Catching falling stars: A human resource response to social capital’s detrimental effect of information overload on star employees.” Academy of Management Review 37, no. 3 (2012): 396-418.

vii. Joo, Harry, Herman Aguinis, Joowon Lee, Hannah Kremer, and Isabel Villamor. “HRM’s financial value from obtaining more star performers.” The International journal of human resource management 33, no. 21 (2022): 4179-4214.

viii. Groysberg, Boris, Linda-Eling Lee, and Ashish Nanda. “Can they take it with them? The portability of star knowledge workers’ performance.” Management Science 54, no. 7 (2008): 1213-1230.

ix. Prato, Matteo, and Fabrizio Ferraro. “Starstruck: How hiring high-status employees affects incumbents’ performance.” Organization Science 29, no. 5 (2018): 755-774.

x. Downes, Patrick E., Eean R. Crawford, Scott E. Seibert, Adam C. Stoverink, and Elizabeth M. Campbell. “Referents or role models? The self-efficacy and job performance effects of perceiving higher performing peers.” Journal of Applied Psychology 106, no. 3 (2021): 422.

xi. Brown, Jennifer. “Quitters never win: The (adverse) incentive effects of competing with superstars.” Journal of Political Economy 119, no. 5 (2011): 982-1013.

xii. Call, Matthew L., Elizabeth M. Campbell, Benjamin B. Dunford, Wendy R. Boswell, and R. Wayne Boss. “Shining with the Stars? Unearthing how group star proportion shapes non-star performance.” Personnel Psychology 74, no. 3 (2021): 543-572.

xiii. Kehoe, Rebecca R., and Daniel Tzabbar. “Lighting the way or stealing the shine? An examination of the duality in star scien tists’ effects on firm innovative performance.” Strategic Management Journal 36, no. 5 (2015): 709-727.

xiv. Li, Yuan, Ning Li, Chuanjia Li, and Jingyu Li. “The boon and bane of creative “stars”: A social network exploration of how and when team creativity is (and is not) driven by a star teammate.” Academy of Management Journal 63, no. 2 (2020): 613-635.

xv. Boekhorst, Janet A., Nada Basir, and Shavin Malhotra. “Star light, but why not so bright? A process model of how incumbents influence star newcomer performance.” Academy of Management Review 49, no. 1 (2024): 56-79.

xvi. Grigoriou, Konstantinos, and Frank T. Rothaermel. “Structural microfoundations of innovation: The role of relational stars.” Journal of Management 40, no. 2 (2014): 586-615.

xvii. Azoulay, Pierre, Christian Fons-Rosen, and Joshua S. Graff Zivin. “Does science advance one funeral at a time?.” American Economic Review 109, no. 8 (2019): 2889-2920.

xviii. Gignac, Gilles E. “The number of exceptional people: Fewer than 85 per 1 million across key traits.” Personality and Individual Differences 234 (2025): 112955.