Please enter your email in order to download this publication.

There’s a yawning gap between the concept of employee development and its execution at most companies. Despite spending billions of dollars on development activities, companies have few tangible benefits to show from their investment.

Our talent practices audits of companies globally show that development planning is the least effective talent practice by a considerable margin.

A key reason for that situation is that HR leaders are somewhat delusional about how managers will approach development planning. We think they will set high quality development plans because we’ve given them resources and training. We’ve told them that experiences matter most, so we trust that they’ll use them as a key development tool. We assume that they believe there’s a business case for developing employees and genuinely want to grow their team members.

Our assumptions about employees are equally unrealistic. We believe that the average employee can accurately guide his or her own development. We assume that they will use the expensive self-learning resources that we’ve provided. We think that they will diligently pursue the activities listed on their development plan.

These and other delusions guide how HR designs and executes employee development processes and are a primary reason that they don’t succeed. Successful development planning requires that we more accurately assess what’s reasonable and make six changes in how we develop employees.

1. Radically Reduce Your Expectations

There’s strong alignment among HR leaders about the value of employee development. In fact, it’s the primary reason most HR leaders give for being in the HR profession. HR has also spent significant time building employee development tools and helping others to complete development plans.

Now, consider the experience of the average manager or employee. They focus on development planning once a year, often at the end of a performance review. That process may not be the same one they saw in their previous company and might not even be the same process they saw last year.

The manager, who likely experienced little development planning in her own career, has no idea what a good development plan looks like. While she may believe in development, your approach feels a little “corporate” to her. She’ll comply, if she has to. Of course both manager and employee know that even if the plan is earnestly completed there are few consequences for not achieving it.

HR’s strong beliefs and familiarity with the topic feed our delusions about how others will behave in this process. Reducing your expectations means setting them at a level that the average manager can reasonably be held accountable to achieve.

There is a powerful first step in setting realistic expectations:

Set one development goal: It’s unlikely that an employee’s achieving their third most important development goal will deliver anywhere near as much value as completing their most important goal. It’s also unlikely that the average employee will actually complete more than one major development activity.

Given those facts, radically reduce your expectations for what should be accomplished and ask managers to set just one development goal for each employee.

That one goal should follow the typical tenets of good goal setting – be measurable, experienced- based (see recommendation #5 below) and achievable. It’s also helpful to state if the development goal is intended primarily to increase current performance or to develop capabilities for a future role.

Is having just one development goal setting expectations too low? Maybe. Once 80% of your company is flawlessly completing their one development goal, feel free to increase your expectations.

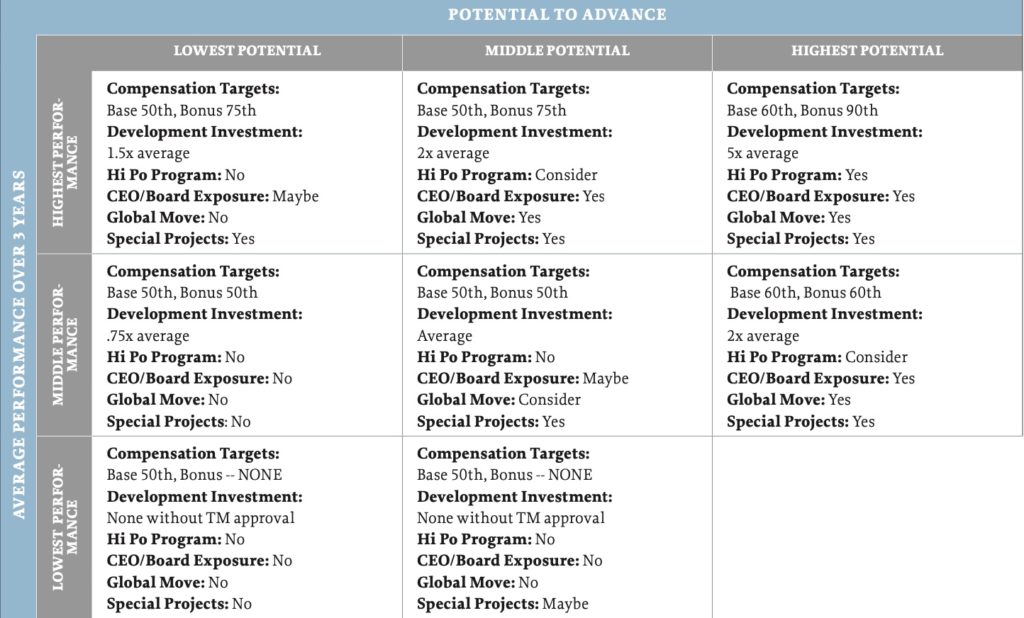

Figure 1: Talent Investment Grid: Example

2. Differentiate Your Development Investment using a Talent Philosophy

It’s the rare executive team that has discussed and agreed on their company’s Talent Philosophy or “rules of the road” for managing talent (see What’s Your Talent Philosophy).

A company’s Talent Philosophy defines the relative importance of performance and behaviors, describes how much they differentiate their development investment and defines how much accountability and transparency they expect in talent management processes.

Without a Talent Philosophy in place, managers’ individual talent philosophies will decide who gets developed and how. As managers apply their widely different approaches, it will send employees conflicting and confusing messages about your company’s rules for success.

Focus on differentiation: One part of a Talent Philosophy describes how your company will invest in employees with different levels of performance and potential. Will high potential employees receive twice the development investment of average potential employees? Five times the investment? How will the investment differ between average performers and high performers?

Make your Talent Philosophy real by using the Talent Investment Grid (TIG) (Figure 1) to allocate your company’s developmental opportunities. Think broadly when completing this grid and include not only the obvious development tools like classes and programs, but also powerful developmental levers like exposure to the CEO and Board.

The TIG should set investment targets, not specific requirements, for those in each of the nine boxes. Your goal is that those with similar levels of potential and performance receive a relatively similar level of investment.

If you don’t use a 9-box grid , simply apply this same approach to whatever categorization of performance and potential that your company uses.

3. Let Managers Set Development Goals

Employee led development is the default approach in many organizations. While seemingly logical and even empowering, employee led development is the approach that’s least likely to build your organization’s critical capabilities.

Managers should lead the development process because they’re best positioned to accurately assess their direct reports’ development needs. There’s conclusive science that individuals are the least accurate assessors of their own performance and behavior. Asking employees to create their own development plan ensures an inaccurate starting point and potentially misdirected efforts.

A manager should also have more accurate insights to which capabilities are critical for the company’s success. They should apply their knowledge about their function’s or group’s needs to create the employee’s development plan. The employee’s interests are inputs to that plan but the organization’s needs must take precedent.

4. Double-Down on Experiences

There’s very solid research that we learn more from experiences than from other types of development. Many companies communicate this belief but few structure development planning to actually enable it.

Traditional competency models work against using experiences for development. If success is described in the bite-sized nuggets favored by competency models then, by definition, the development conversation isn’t about experiences (see Life After the Competency Model).

Shifting your company’s development approach to one that’s focused on experiences requires meaningful effort. Two tactics that can help are:

Make experiences the language for development: In the tool you use for development planning, make experiences the default language of development. What is Mary’s experience plan for this year? What one experience does Mary need to achieve to succeed in this role or advance to another? What one development experience will you give Mary this year? How will you measure the success of Mary’s experience?

This may seem like a facile approach but it reinforces that experience are synonymous with development.

Competency models define job success as gaining static pieces of knowledge or skills (i.e. Strategic Agility, Political Savvy). Experiences describe what must be demonstrated to prove that competence (i.e. Create a New Product Marketing Plan, Manage a Project Across Diverse Geographies). These are two very different approaches and the average manager isn’t able to create a development plan that bridges them.

Increasing the focus on experiences implies that you decrease your focus on other types of development. That million-dollar suite of online courses, videos and resources you purchased? Rather than renew that license, use those funds to better identify and move people through actual developmental experiences.

Create Experience Maps: Shifting your organization to experience-based development is far easier if you create “experience maps” for each function. An experience map describes the five to ten key experiences that are the building blocks of success for a function.

These maps are practical, experience-based guides for development and career planning. They make it far easier to emphasize development through experiences because career paths are defined by those experiences, not by competencies.

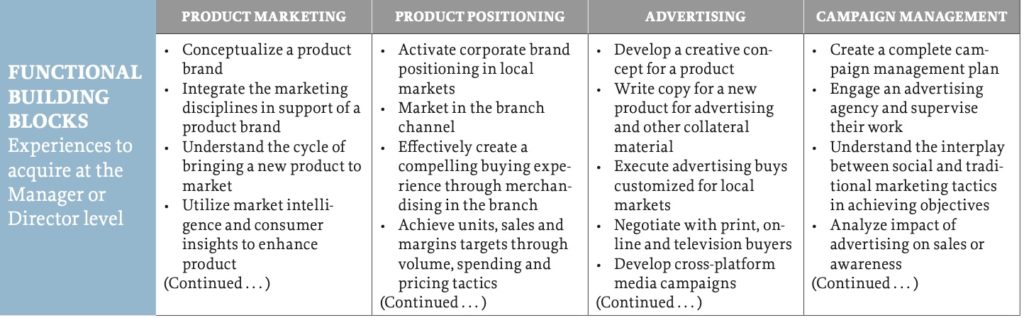

Figure 2: “Building Blocks” Section of a Marketing Experience Map

For example, within the Marketing function one key building block might be Advertising (See Exhibit 2). To succeed in Marketing you’ll need some capability in advertising. How much you’ll need depends on your career goal.

If you want to be an advertising specialist (i.e. a VP of Advertising) you’ll likely want to acquire every experience in the advertising area. If you want to be the SVP of Corporate Marketing, you might need some advertising experiences and some experiences in other Marketing sub-functions.

The experience map defines the few experiences that are essential for functional success. To create a development plan from an experience map, you simply identify which experiences are still needed for job or career growth and find the project, exposure or assignment that will most quickly build that experience.

5. Create High Potential Development Plans in Talent Reviews

Great development planning is especially critical to accelerate the development of your highest potential talent. Use your talent review discussion to ensure they have a detailed and substantive plan.

You’ve just had a great conversation about Suzie Hi-Po’s strengths, weaknesses and ambitions. With these facts on the table it’s the ideal time to ask, “What one development experience would best accelerate Suzy’s career growth?”

This discussion will produce a superior development plan because you’ve tapped into the collective wisdom of the group. Not only will more development ideas likely surface, the collective input of the group should neutralize any of the direct manager’s biases.

The group’s decision should become the individual’s development plan and be recorded as the group’s commitment to develop them. Recording this development commitment and revisiting it at the next talent review meeting also helps to ensure accountability for follow through.

6. Make Managers Accountable for Development

Development plans typically crash at the intersection of good intentions and busy managers. We shouldn’t assume this situation will change until we clarify who’s accountable and with what consequences.

Managers are accountable: It’s a manager’s job to ensure that their team members are being developed both to perform their current job and, if appropriate, their next role. If an employee doesn’t complete their one development step, the responsibility lies with the manager.

The manager is accountable because their role is to ensure that the organization has the capabilities it needs to win. If they fail in their efforts to build those capabilities – independent of the reasons why — they need to take accountability.

Why isn’t the employee accountable? They are, but in a different way. The employee who resists efforts to (or isn’t capable of) improve their performance or behaviors is sending a clear signal about their future value to the organization. Their consequence is a plateaued career or a pink-slip in the next round of layoffs.

For actual completion of the experience: The manager’s accountability is that the employee actually completes the development experience. One can assess completion in a multitude of ways but one suggestion is for the manager’s manager to assess this using data that the manager provides.

With career consequences: Accountability means little unless there are meaningful consequences for achieving or not achieving a result. The consequence for employee development results should be the acceleration or deceleration of career growth.

A manager’s proven ability to grow talent, over time, should be a key criterion in the talent review discussion about potential to advance. Its weight should be at least enough to “round up” or “round down” a potential rating.

Let’s Get Real Development Results

The business case for employee development is both intuitive and compelling. It’s essential to produce the capabilities a company needs to remain competitive. It’s a primary driver of employee engagement. It can quickly improve an individual’s performance and behaviors.

Yet no matter how compelling the business case, employee development will become effective only when we align our mindset and practices with corporate reality. And, we place true accountability with managers to grow the quality and depth of their teams.

References:

- Global HR Census, 2019, Talent Strategy Group

- McCall, Morgan W., Lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. Free Press, 1988.