Please enter your email in order to download this publication.

“The increasing popularity of 360-degree assessments seems to rely on a rock-solid stream of logic. Leaders’ behaviors are important to the organization because well-behaved leaders balance what gets done with how things get done. This balance increases their own effectiveness and their team’s engagement and performance, which translates into superior financial results.

So, if we regularly give leaders 360-degree feedback, they will be motivated to improve their behaviors and the average quality of leaders and results will continually increase. It is a wonderful theory, but it bears little resemblance to reality.”1

That quote starts the chapter in One Page Talent Management about 360 assessments that Miriam Ort and I wrote nearly 15 years ago. It is just as applicable today. Despite the tens of millions of dollars that companies spend annually on 360 assessments, they typically don’t deliver changed behavior or higher performance.

You might resonate with that claim or you might ask to see the science that backs it up. The best science is found in a meta-analysis of 24 different studies on 360s that measured managers’ assessment scores over time. That research found only very small score changes on average between a manager’s first 360 report and their second one. And, even those small changes didn’t meet the burden for statistical significance.2

We also know that positive change can be most difficult for those who need it the most.3 The classic Dunning Kruger experiment was replicated with those who were assessed as low in emotional intelligence, a common 360 assessment category. Those low scoring individuals were quick to argue about the relevance and/or accuracy of their feedback and were the least likely group studied to try to improve.4

Getting the Value from 360s

Those findings don’t prevent 360s from helping leaders to change and grow. They do mean that assessment-based 360s are designed to accurately assess people – not to develop them and not to make it easy to act.

If we want 360 feedback to help leaders change their behaviors, let’s start with this lofty goal: A 360 report should tell the leader exactly where to focus their efforts and exactly how to improve. It should create the lowest possible amount of cognitive dissonance and fear, and the most possible psychological safety and motivation.

If a 360 report meets that very high standard, it means that a leader has all the information they need to act and very little resistance created by how the information is presented. Only consequential accountability is needed to help the leader start the change.5

Creating the Ideal Developmental 360

We specifically use the term “developmental 360” to distinguish this concept from 360s designed to assess competence. Both are valuable but for very different reasons.

We believe the hallmarks of a truly developmental, science-based 360 process and report are:

1. Direct, don’t rate: Many popular 360’s rate how well a leader performs a particular competency or behavior.6 For example, a leader would know they are rated a 4.2 on a 5-point scale. While that rating may be accurate, the practical challenge is that it provides no directional advice to the participant.

Does a score of 4.2 out of 5 tell a leader that they should do more of that behavior? Do less? Not change it? The science is clear that being rated does not motivate change, so there is no development value in using a classic rating scale.

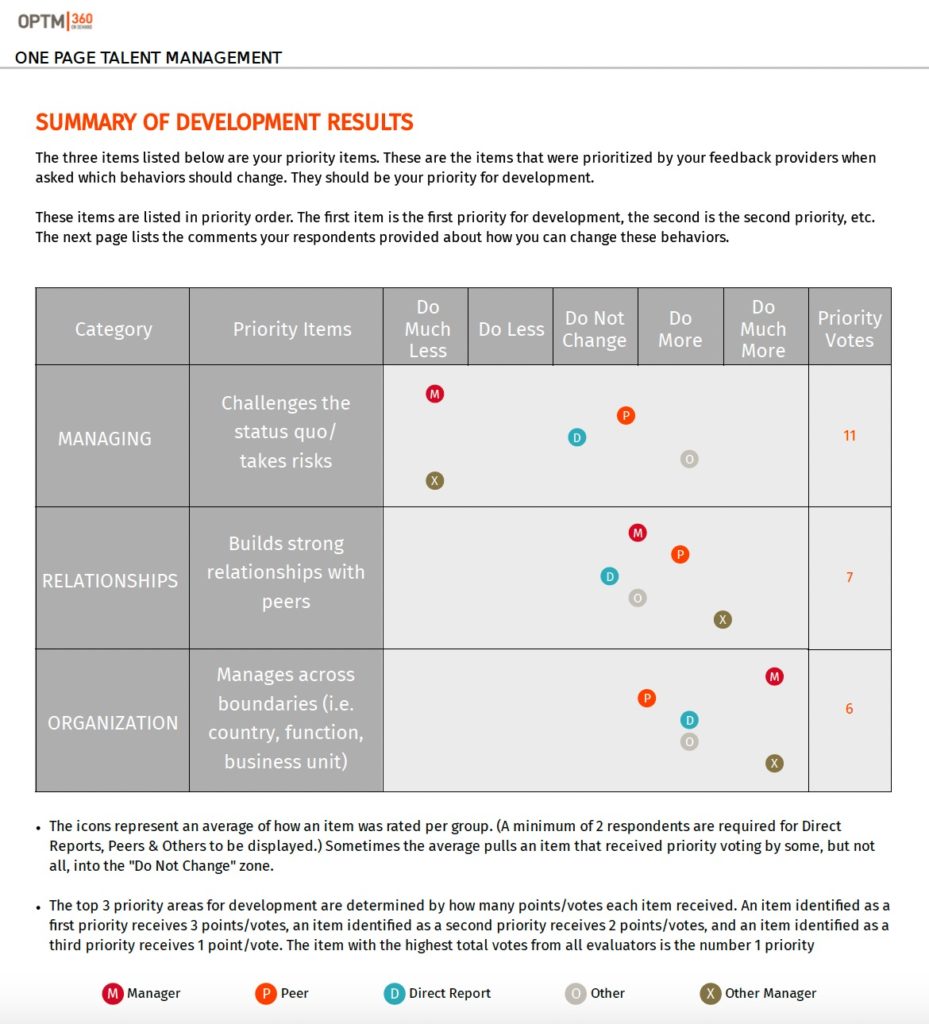

Our advice: We believe that the scale of a developmental 360 should tell a leader how to adjust their behavior – Do More, Do Less or Don’t Change. That scale instantly provides the leader with direction about what to do. When combined with the prioritization and verbatim comments guidance below, it makes it easy to understand what to change and how to change it.

2. Prioritize what co-workers care most about: Assessment 360’s often include a list of the participant’s top 5 or bottom 5 scores, with the suggestion that these are the most important areas to work on. A more accurate way for a leader to understand their co-workers’ priorities for their change is to ask them about their priorities for their change!

Our Advice: We recommend that a developmental 360 ask the assessors to rate their top three priorities for change across the items listed. Those priorities can then be averaged across assessors to show the participant which two or three items should be prioritized for change.

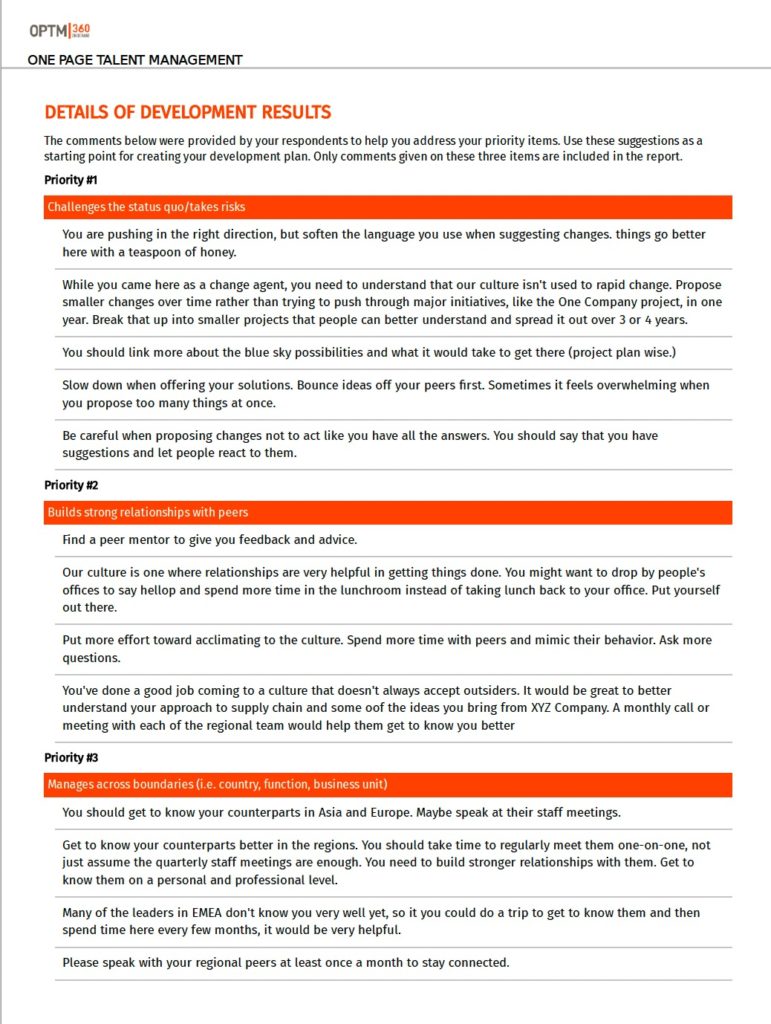

3. Give specific advice for change, linked to priorities: Even with prioritized Do More/Do Less advice, it can be challenging to determine exactly what the participant should do differently.

Some 360 providers will include generic guidance based on the item’s score being higher or lower. That guidance is not inaccurate but it’s the same advice generated for anyone who scores at that level.

So, it’s theoretically correct but practically questionable. It doesn’t consider practical factors like the company’s culture, the participant’s relationship with their peers, etc.

Our advice: Once assessors have given Do More/Do Less guidance and ranked their priorities for change, ask them to tell the participant exactly what they can do to improve those two or three prioritized behaviors. That guidance can be collated for every item assessed so that the participant gets specific, relevant, practical advice for change.

4. Forward-guidance, not feedback: Both the Do More/Do Less scale and the change guidance are designed to reduce a leader’s resistance to change. We know that managers who receive lower scores on 360s often believe that the feedback is not accurate and they are less motivated to change.7

We also know that, contrary to the belief that managers will see low feedback and be motivated to change (control theory), the results from research on 360s suggest that’s typically not the case (See the Sidebar: Do difference in self-rating versus other ratings create motivation?)

This means that when a leader sees their 360 results they create little or no motivation to change. If the goal of a 360 is to create behavior change, assessing someone’s behavior is unlikely to produce that outcome.

Our advice: You can ensure that your 360 process is developmental by using forward-looking comments and a forward-looking scale to make it easier for leaders to change. Assessors should be told to focus their suggestions for change on behaviors that the participant should demonstrate in the future, not to critique their past behaviors.

5. Measure what matters most: Assessment designers include multiple items for each 360 topic to ensure that the assessment accurately measures what it says it measures. While that’s the correct approach, it makes assessment 360s very lengthy – often nearing 100 items.

That number of items may be needed to accurately assess a leader, but you can develop a leader using far fewer items.

Our Advice: Identify the 10 – 20 behaviors that matter most to success in your organization. State them in a neutral way (i.e. “communicates about strategy” not “effectively communicates about strategy”).

Use the Do More/Do Less scale and use the comments to provide additional detail for change (i.e. Communicates about strategy. Do Less. “We hear her discuss the strategy at a high level every week but we need her to communicate more about her plans to execute it. A weekly update would be great.”)

6. No norms: If you use the Do More/Do Less scale recommended above, norms are irrelevant. If most people are rated “Do More” and a leader is rated “Do Less,” that provides no practical advice for their development.

If you think that comparing an individual’s scores to others’ scores is motivational, it typically isn’t (see sidebar). The science says that gaps between one’s self-assessment and others’ assessments generate little or no motivation for change.

Our advice: Do not report norms, either those from within your company or those from the outside. They add complexity without adding value.

7. No self-assessment: The science is incredibly clear that people are woefully inaccurate about their own behaviors. Men overrate themselves compared to women. Older people overrate themselves compared to younger people. Those at higher levels in a company overrate themselves compared to those at lower levels. Those with high self-esteem overrated their performance vs. those with low self-esteem.8 We could go on.

Given how clear and persistent these finding are, why do we ask for self-assessment on 360s? The science is clear that there is no motivational benefit from seeing the gap between one’s own perceptions and others’ perceptions.

Our advice: Do not include self-assessments but explain to participants and assessors the science-based reason for that choice.

————————————————————————————————-

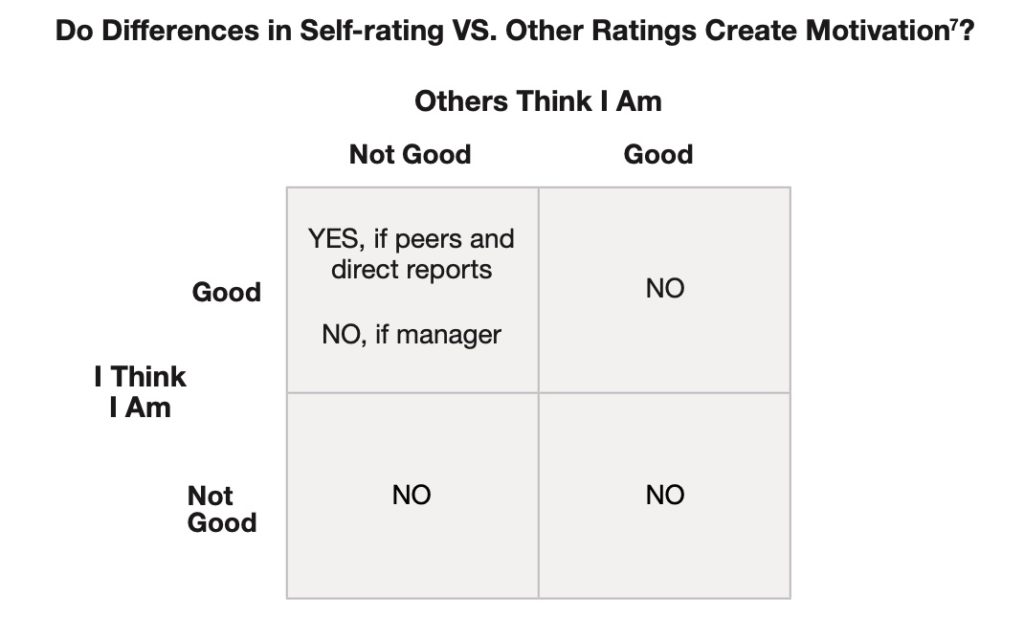

Gaps between self-assessment and others rarely motivate action

A logical assumption that underlies using self-assessments in 360s is that a manager will be motivated to change if she sees gaps between her own assessment of her behaviors and others’ assessment of her.

Rather conclusive science suggests that is not true as shown by the chart below. Only in very limited circumstances (high self-assessment and low assessment by direct reports) is any motivation to change created.

What a Great Developmental 360 Looks Like

If we design a developmental 360 with the attributes described above, it will look very much like the OPTM360 we originally shared in One Page Talent Management. Within the first three pages of that ideal 360 report, a leader will see their top three Do More/Do Less priorities and get specific, practical guidance from their co-workers about exactly how to change.

How that information is presented should not trigger resistance, since the leader hasn’t been rated and they’re not seeing gaps between their scores and others’ assessments. They won’t be overwhelmed or put off by volumes of data since they’ll see their three priorities first, separated from the rest of their report.

Most importantly, they will have a list of suggestions describing exactly how they can change their behaviors. This not only makes taking development actions easier but also removes their excuse of not knowing how to translate a 4.2 out of 5 rating into an action item.

We know that change is hard for leaders and that the more successful they become the more difficult it can be to change. The approach we describe above is grounded in the best science of human behavior and focused squarely on the goal of making your leaders better faster.

- Effron, Marc, and Miriam Ort. One page talent management: Eliminating complexity, adding value. Harvard Business Press, 2010.

- Smither, James W., Manuel London, and Richard R. Reilly. “Does performance improve following multisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis, and review of empirical findings.” Personnel psychology 58, no. 1 (2005): 33-66.

- Heidemeier, Heike, and Klaus Moser. “Self–other agreement in job performance ratings: A meta-analytic test of a process model.” Journal of Applied Psychology 94, no. 2 (2009): 353.

- Sheldon, Oliver J., David Dunning, and Daniel R. Ames. “Emotionally unskilled, unaware, and uninterested in learning more: reactions to feedback about deficits in emotional intelligence.” Journal of Applied Psychology 99, no. 1 (2014): 125.

- Effron, Marc. “The Accountability Ladder.” https://talentstrategygroup.com/the-accountability-ladder-a-simple-yet-powerful-tool-to-drive-insights-awareness-and-action/

- See https://www.shl.com/solutions/products/product-catalog/view/mfs-360-ucf-standard-report/and https://talentforgrowth.com/360-degree-feedback/ for examples of this rating approach. There is no pejorative intent in selecting these specific companies’ reports. Their report scale simply meets the criteria described.

- Brett, Joan F., and Leanne E. Atwater. “360° feedback: Accuracy, reactions, and perceptions of usefulness.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86, no. 5 (2001): 930.

- Fleenor, John W., James W. Smither, Leanne E. Atwater, Phillip W. Braddy, and Rachel E. Sturm. “Self–other rating agreement in leadership: A review.” The Leadership Quarterly 21, no. 6 (2010): 1005 1034.